Coding Patterns for Trunk-Based Development

Trunk-Based requires committing unfinished work to the master branch: let's explore the fundamental coding patterns that enable this ability to continuously keep our code in a release-ready state.

Hello, developers! 🚀

Welcome back to the Learn Agile Practices newsletter, your weekly dose of insights to power up your software development journey through Agile Technical Practices and Methodologies!

Before starting, let me remind you that I just launched my Test-Driven Development 101 5-day Email Course!

With this course, you will effectively learn what TDD is, for real: what's the objective of this practice, how the TDD process works, and how it enables you to achieve better software. The course goes beyond theory with interactive quizzes and flashcards for active learning, providing practical tips and suggestions for practicing with katas.

As a subscriber to my newsletter, you can have it with a 10EUR discount!

Now, let's dive into today's micro-topic!

Branches make integration more complex

Branches are a very powerful tool, especially when your version control system is Git, offering developers a way to change the code in an isolated copy from the main branch. However, their convenience has led to overuse, with branches often lasting for days or weeks, diverging a lot from the master branch and leading to merging hell, slow and hard integration of code, long and hard code reviews, etc.

This probably happened because of how useful is a feature branch approach in the Open Source world - but in that context, changes come from people we don’t know and trust, with different objectives, timezones, etc. In the software team of a company, the situation should be the opposite, and the team members should have a high level of trust in each other. Unfortunately, in most cases, feature branches are considered a standard, and you also face GitFlow (the devil itself!) and other complex Git strategies.

This approach has several drawbacks, for example:

Slow Feedback Loop: code reviews are coming too late and are too long, and the same happens for the feedback about how well our new code integrates with the existing one - and also feedback from users about what we produce is slow.

Merge Hell: when the feedback about our work comes so late, merge hell happens; reviews are slow and painful, with a lot of discussions around choices from old days or weeks - or dropped discussions to not keep the change stuck.

Lower Collaboration: developers get used to working in isolation for a lot of hours every day, and need to take care of putting their code with the one from others not very often - when we call code “my code” it’s a red flag.

Slow Time-to-Market: As a consequence of previous problems, the time to market for our software is slow.

As most of you might already know, the alternative is Trunk-Based Development: committing the code directly to master, or on branches that last no more than one day.

Decouple releases from launches

When we use Trunk-based development, integrating our code in the main branch becomes something very common, done multiple times per day, and totally automated - otherwise it wouldn’t be sustainable to integrate so much. Automated tests are a must in this context, for example - and it must be a test suite we trust.

When it comes to Trunk-based development, I usually see developers struggle mainly with two ideas:

Committing directly to the main branch

How to release work in progress

The first point is hard to accept because we are used to taking advantage of branches to “protect” the master branch - but it’s also usually easier to accept for newcomers to Trunk-based. The second problem, instead, is a lot harder.

The fact is that we have been taught that a release is something that can only happen at the end of the software development cycle of an entire feature: if we think of the software development cycle of work (analyze-develop-test-release, to make a simple example), all of us learned to think about this cycle at an entire feature level; this makes most of us think that this cycle is costly, and we don’t realize that it becomes costly because we do it after a lot of changes.

The reality is that nothing stops us from reducing the scope of the software development cycle from as big as an entire feature (or more) to as little as a day or an hour of coding: thanks to automation, it’s trivia to achieve such objective today from a technical point of view, and the only real obstacle is our mental approach to this topic.

Another strong belief we all have is that we usually think that the deployment/release of the software is tightly coupled to the day of launch decided by marketing/business: this usually leads to hard sync work to ensure that the commercial side and the technical side reach a deadline both at the same time and then a big bang release with long nights to put the software in production just before announcing it to the world. It doesn’t have to be this way: we can separate deployments and releases from the business launch which makes the life of our company a lot easier, enabling a shorter feedback loop on our decisions and removing the need for a complete sync between two very different kinds of work.

How do you send unfinished work to production?

Trunk-based development implies integrating code on the main branch at least once a day, even if it’s a small step forward. This often means merging changes before a user-facing feature is fully developed and ready for deployment. As a result, handling unfinished work—the latent code that forms part of an incomplete feature but is present in a live release—becomes crucial.

Usually, developers are worried about latent code, as it introduces non-production quality code into the released executable. However, we still need to ensure that all code merged into the mainline is of production quality. This includes accompanying tests to validate the code": latent code may never be executed in production environments, but it is still exercised during testing.

The following is a list of the most common patterns used to merge unfinished work on master while keeping it hidden from the user while ensuring the release is stable and releasable: it’s not an exhausting list, but those are the practices I’ve used (and seen use) the most in my career.

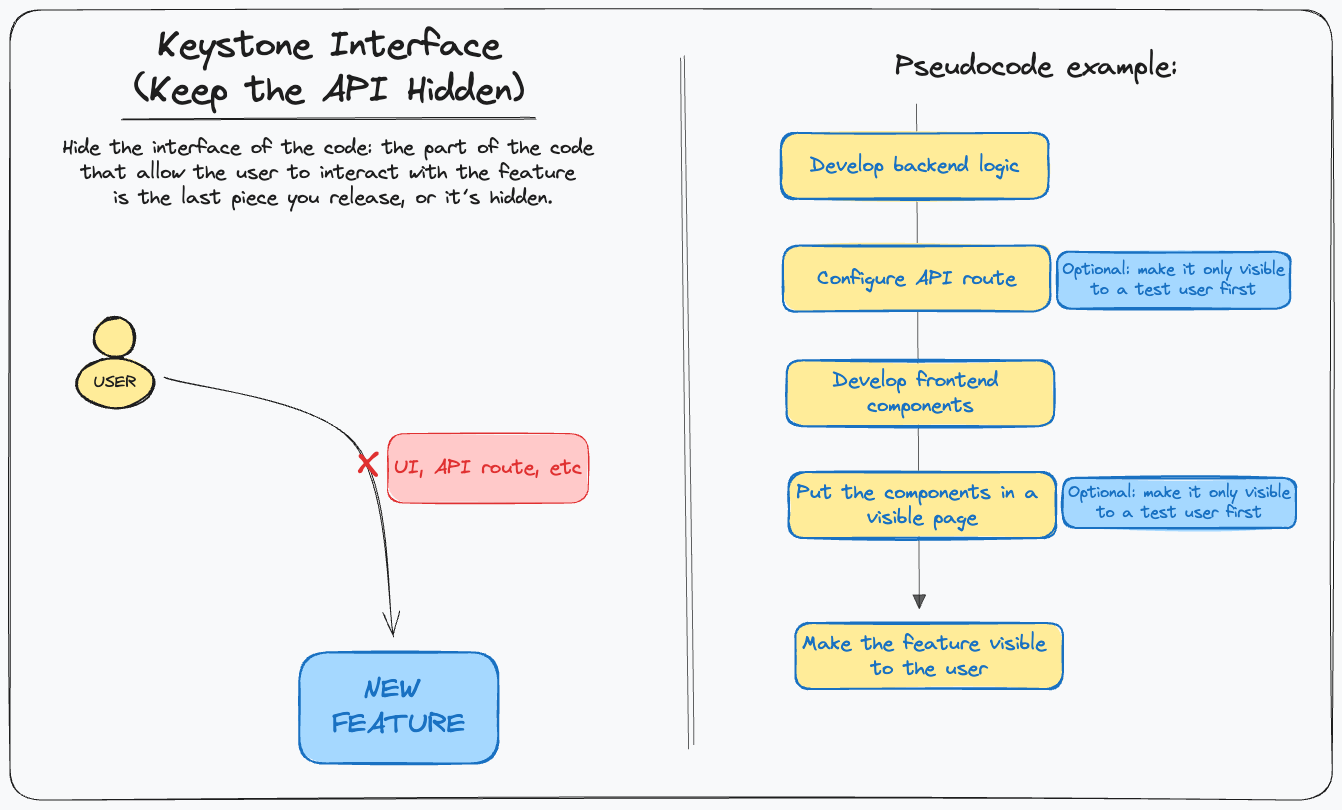

Keep the API hidden

The first, straightforward idea is called Keystone Interface (aka. Keep the API hidden). The idea is pretty simple: given a new behavior to be added to the software, make sure that the interface that allow the user to interact with that behavior is the last piece released in production. It’s a very good solution for new features.

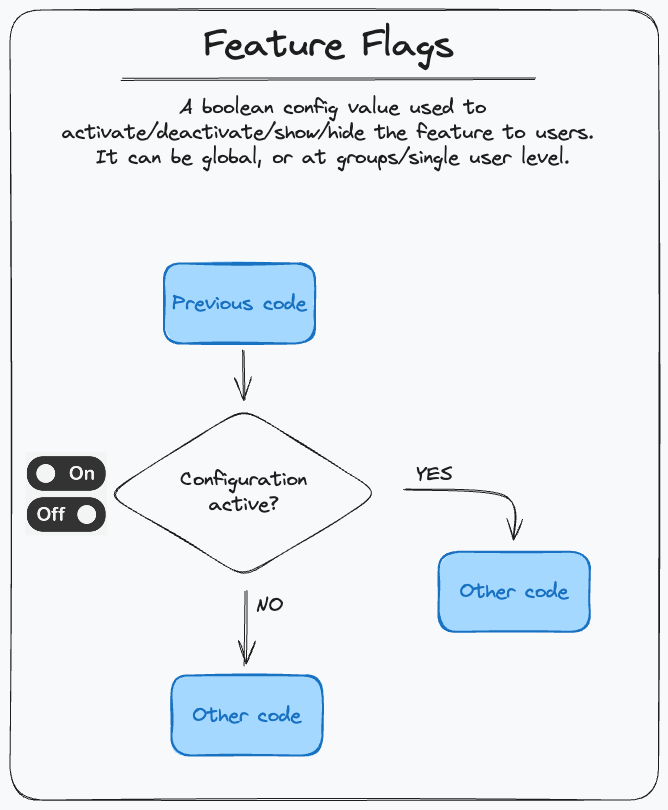

Feature Flags

This is probably the most famous pattern of this list: a feature flag is not much more than a boolean value, usually put in a configuration, that decides if a specific code is executed or not (YES, it’s an IF 😃). Thanks to this configuration, we can release the feature while it is turned OFF, and turn it ON later. It can be used for entire features or smaller new behaviors, and it’s a good idea to implement a Strategy Pattern to keep the flag logic encapsulated - usually, it’s also a good idea to set this pattern up as the first thing before developing the feature.

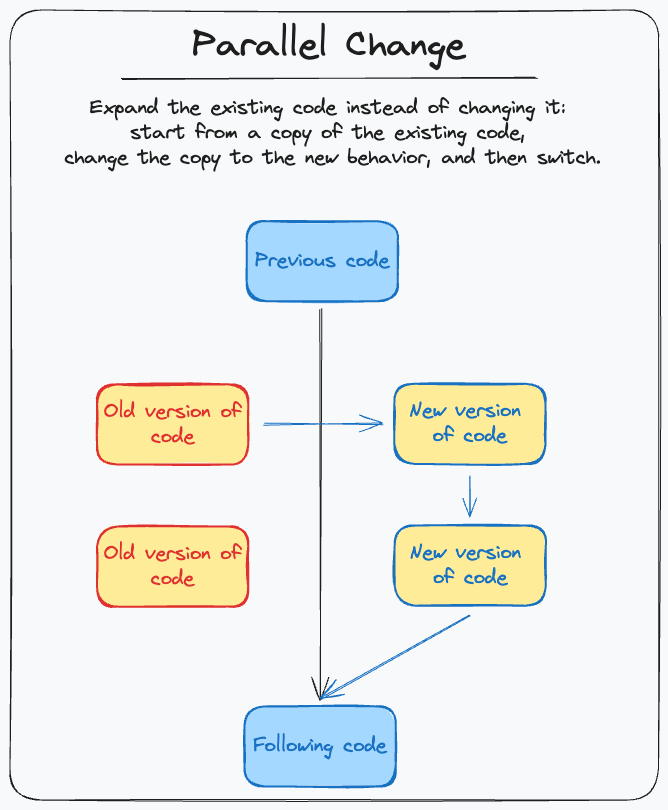

Parallel change

The third pattern is slightly more complex than the previous one: Parallel Change is a refactoring technique we can take advantage of to release work in progress easily. The idea is simple: instead of changing an existing piece of code, make a copy of it and change the copy. When the new version is ready, replace the original with the new one. This is a good approach when we have to change a complex piece of code adding a new important piece of behavior.

Branch by abstraction

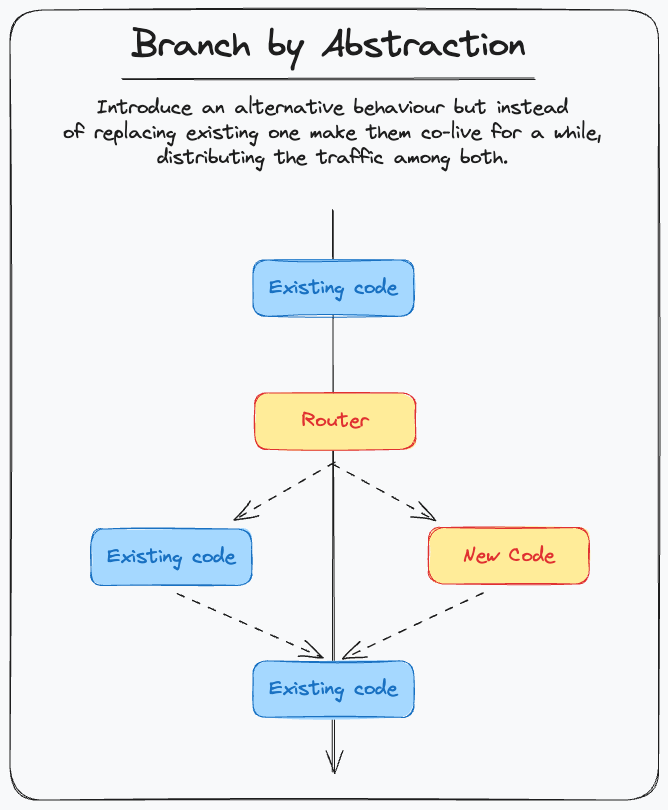

This pattern has some similarities with both Feature Flag and Parallel Change: when using “Branch by Abstraction”, we start with a Parallel Change. The difference is that, once we are ready with the new version, we create a Router class that drives the traffic between the two versions, and we progressively move the traffic from the old to new version (for simple cases, it can be done with a boolean config Feature Flag). Once the migration is completed, we also delete the old version. It’s a great addition to Parallel Change when we are changing a delicate feature (think checkout).

Dark launch

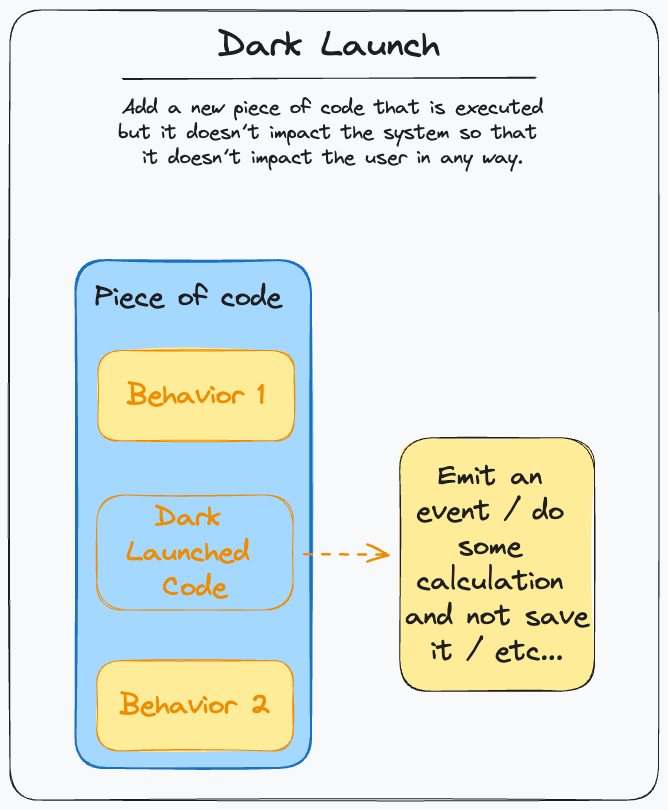

With Dark Launch, we can introduce new behaviors in a safe, isolated way from the system. This pattern suggests releasing the new behavior in a way that doesn’t impact the system: for example, it might trigger an ignored event at the end, roll back any change to DB, or even better fake those changes and build a dedicated log to check that it worked as expected. This is good for some architectural changes (such as introducing events) or contained behavior that doesn’t impact much the existing one (in which case I would prefer a Parallel change).

Canary Releases

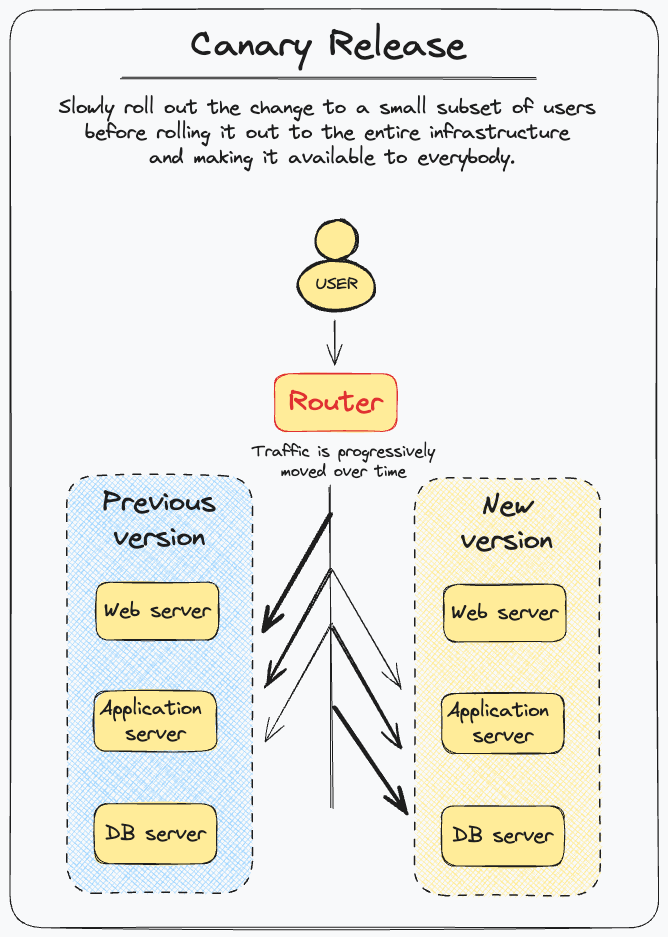

We can simplify the Canary Release pattern by defining it as the “Branch by Abstraction” pattern at the infrastructure level: with this pattern, we can release the new version of our application on a new instance/server. When deployed, this instance is ignored - then, a router starts sending a bunch of requests to it, and progressively raises the number of requests until it reaches 100%; at this point, the old instance is turned off and thrown away.

🧠 Test Yourself in 1 minute:

💡 Did you know? An interactive activity, like quizzes or flashcards, can boost your learning!Take advantage of our set of Flashcards dedicated to this topic: read the word and try to describe its definition - then turn the card to check the correct one for feedback 😲 Don't miss out on the opportunity to boost your learning—try now!

Drawbacks of long-living branches are…

Insights Recap

Feature branches have become a standard thanks to Open Source: it perfectly suits that context but doesn’t suit well a software development team context where the level of trust and alignment of objectives should be a lot higher

Some drawbacks of long-living branches:

Slow Feedback Loop

Merge Hell

Lower Collaboration

Slow Time-to-Market

The alternative is Trunk-Based Development: committing the code directly to the main branch, or on branches that last no more than one day.

Hardest things to accept about Trunk-Based Development:

Committing directly to the main branch, because we are used to “protecting” the master branch

How to release work in progress, because we have been taught that a release is something that can only happen at the end of the software development cycle of an entire feature

We can reduce the scope of the software development cycle from as big as an entire feature (or more) to as little as a day or an hour of coding.

We can also separate deployments and releases from the business launch.

How do you commit unfinished work? We need to learn how to merge unfinished work on master while keeping it hidden from the user. Some of the most common patterns are:

Keep the API Hidden: make sure that the interface that allows the user to interact with the new code is the last piece released.

Feature Flags: a config boolean value that can be turned ON/OFF to decide if a behavior is visible or not.

Parallel Change: instead of changing an existing piece of code, make a copy of it, change the copy, and replace the old version when done.

Branch by abstraction: start with Parallel Change, but then make the two versions live together for a while, progressively moving the traffic from old to new.

Dark Launch: release a new behavior in a way that doesn’t impact the system by either reverting what it does or creating an output that is ignored by the rest of the parts.

Canary Releases: a sort of “Branch by Abstraction” at the infrastructure level; after a change, build the new version of the system and release it on a new instance with zero traffic at first - then progressively move traffic from old to new instance, and kill the old instance when not used anymore.

Until next time, happy coding! 🤓👩💻👨💻

Go Deeper 🔎

Legenda

📚 Books

📩 Newsletter issues

📄 Blog posts

🎙️ Podcast episodes

🖥️ Videos

👤 Relevant people to follow

🌐 Any other content